The miller’s daughter had been left a ring by her mother which was slightly too big for her finger, so she often took it off and put it on; took it off and put it on. One day she walked by the millpond and heard croaking, high and low, for all the world like a conversation. Nearer she crept and nearer, fingers idly playing, till she saw a knot of toads: one large one surrounded by many smaller ones, for all the world like a king and his court. She laughed, but, laughing, slipped on the soft pond edge and plop! in she went like a toad, and plip! more quietly, in went the ring.

She flopped and floundered, floundered and flopped, and made it back to the bank, where the smaller toads with their high-pitched croaking sounded like they were laughing, till the large one, with one deep croak, silenced them. When she sat on the bank, she noticed she had lost a shoe, and it new. Thinking, she took the other one off and put it safe, then waded in and by luck more than judgment found the shoe. Utterly covered in mud, only now did she notice her finger did not shine. Knowing she had trodden the pond bottom thoroughly, she also realised she had probably trodden the ring deep into the mud. And so she flopped and floundered to the bank where she cried and cried, till the tears cleaned her face and restored some of her looks.

The smaller toads had all vanished, but the larger one watched her gravely, and eventually it asked, “Whatever is the matter?”

“Oh,” she sobbed, “I have lost my mother’s ring that she left me, and I likely never to get it back!”

“I should laugh at you as you laughed at us,” said the toad. The miller’s daughter, irked, snapped, “I heard you laughing.”

“I did not laugh,” said the toad.

“No,” said the miller’s daughter, slowly, “you didn’t.”

“If you will promise faithfully to do me a favor when I ask it of you,” said the toad, slowly, “I will find the ring.”

“I promise,” replied the miller’s daughter. Plop! in went the toad.

For days she did not see him, then there he was in her garden, and at his feet the ring. “Oh, thank you!” she cried, and put it on her finger at once.

“I like this garden,” remarked the toad. “It is neat and pretty, with soft, damp soil. And near the pond. May I live here?”

“Of course!” cried the miller’s daughter. “Of course!”

And so began the friendship between a toad and a miller’s daughter. The would have long conversations about whatever took their fancy, and if the miller’s daughter thought he was strangely educated for a toad, she was smart enough not to press the point. From time to time the smaller toads visited the garden, too, and then the knot of toads would form, and the croaking, high and low. Each night after this happened, deep in the dark hours, the miller’s daughter would hear long, hoarse croaks like sobs. Eventually she went down to the garden despite the night air and the dew and found her friend.

“Whatever is the matter?” she asked.

“I have a jewel in my head, and it pains me,” replied the toad.

Now, the miller’s daughter knew that toads carried jewels in their head, and that alchemists and wizards would pay a pretty penny for toadstones, but she had never heard that it pained the toad before. But then, she had never met such a well-educated toad before, so she took it in her stride.

“It must pain you greatly, to cry out so,” she said softly, picking him up and, she thought, noticing a shining beneath the skin on his head.

“It does, and it grows worse,” replied the toad. “I need to ask you—will you take it out for me?”

“But that would kill you!” she said.

“Nevertheless,” he insisted. “I did not cavil when it took me a week and a day to find your ring.”

“No more you did,” she said thoughtfully. “Leave the matter with me.”

She consulted the witch who lived further down the river about how to remove a toadstone. “Put it on a piece of red cloth,” remarked the witch. “If that doesn’t work at least it will soak the blood when you smash its head.”

She walked a long way to consult a cunning man, pretending she was interested in the things he was interested in. “I hear,” she said to him, “that toadstones are sovereign in the curing of fits. Is this true?”

“Only if taken from the head of a living toad,” he said. “Here, I’ll show you.” Alas, all of his demonstrations resulted in the death of the toad, and the miller’s daughter’s spirits fell. Still, she pretended she was interested in the cunning man’s medicines, and walked there every week pretending to study with him and reading his books, but she found no way of removing the jewel in her friend’s head without killing him. And soon she noticed that the cunning man had more than a teacher’s interest in her, so she stopped going.

When she got home, she went to find the toad in her garden. It was coming on night, and the smaller toads had gathered. “My toad,” she said, “I have read and studied as widely as I can, and I can find no way to remove the jewel that pains you that will not result in your death. I do not wish to kill you. You are a good friend to me.

“Are you still of the same mind you were?”

The toad nodded. “There is a way, but if you cannot find it in your heart, then it is not to be found,” he said.

His words turned and turned themselves in her mind till, suddenly, she had an idea. She picked her friend up carefully, and, hoping against hope, removed the jewel with a kiss.

Immediately a young man stood before her, with a ruby in his hand and a grievous head wound. He fell to the floor. The smaller toads, transformed into his friends, and each with rubies in their hands, rushed to surround him, and carried him off. The miller’s daughter rushed to her room in tears, though she knew not why.

Some days later, bandaged but alive, he appeared again in the garden, and held out his hand to the miller’s daughter. “My dearest friend,” he began, “many years ago I unwisely employed a dishonest man in my retinue, who stole a ruby necklace from a sorceress and planted it in my possession. She, finding it among my things, cursed me and my true servants to be toads, with a ruby in each of our heads, until such time as someone. knowing nothing about me, would find it in her heart to remove it.

“You have proved not only to be wise of counsel but wise of heart, and you have learned not to act without thinking, as once you acted by the millpond. Will you, then, come with me, and be my wife?”

“Gladly,” said the miller’s daughter, and in time they came to the young lord’s lands, where he was wonderfully received. They married and become renowned for their kindness and wisdom—and they kept their gardens neat and pretty, with soft, damp soil, for any toads who might be passing by.

***

Jennifer A. McGowan won the Prole pamphlet competition in 2020, and as a result, Prolebooks published her winning pamphlet, Still Lives with Apocalypse. She has been published in several countries, in journals such as The Rialto, Pank, The Connecticut Review, Acumen and Agenda. She is a disabled poet who has also had Long Covid for 15 months at time of writing. She prefers the fifteenth century to the twenty-first, and would move there were it not for her fondness of indoor plumbing.

***

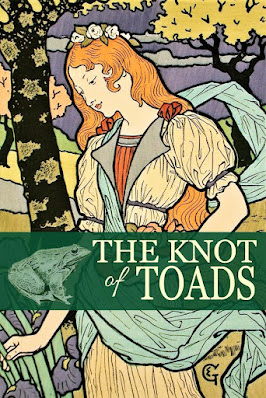

Image is by Amanda Bergloff, using an illustration by Eugene Grasset, 1893.

***

This story was made possible by generous donations by Patreon patrons. We could use some more, so please consider donating. The details are here.